|

|

|

Opening conferenceMedieval Béjaia Center for the Transmission of The Mediterranean Knowledge

Short biographyDjamil Aïssani is a State Doctor of Mathematical Sciences since 1984, Professor since 1988, 1st Dean of Faculty at the University of Béjaia (in 1999) and Director of the LaMOS Research Unit (Modeling and Optimization of Mathematical Systems). He is the Coordinator and Scientific Director of the 1st Algerian Doctoral School in Computer Science (2003 - 2011) and President of the Learned Society GEHIMAB (History of Mathematics in Béjaia, the Maghreb and the Mediterranean - founded in 1991). He is Research Director at the CNRPAH Algiers, Curator of the Mega Exhibition "Scientific Manuscripts of the Maghreb" (2012, currently open at the Centre des Etudes Andalouses, Tlemcen) and co-editor (with Pauline Lebret-Romero and Norbert Verdier) of the special issue "Polytechniciens en Algérie au XIXème siècle" of the international review Sabix (Ecole Polytechnique, Paris), n° 24, December 2019, 170 pages. Abstract« Vidi Buggea che v’é di gran loda »

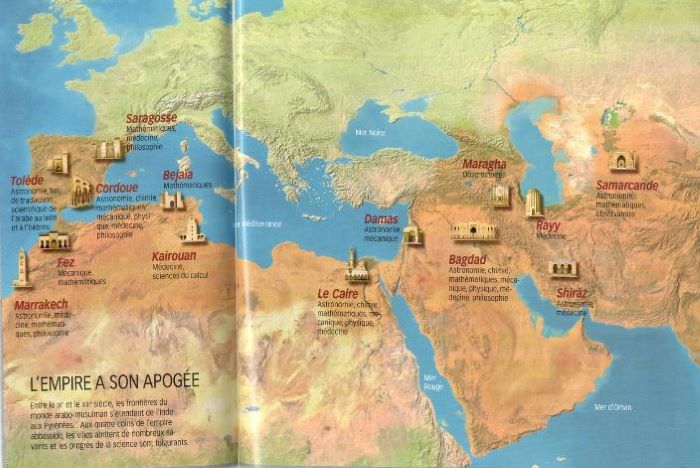

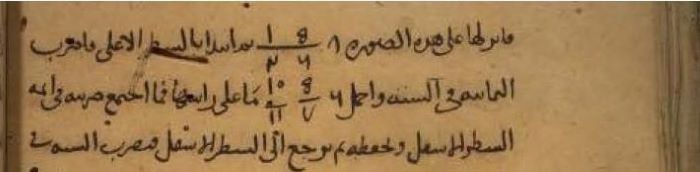

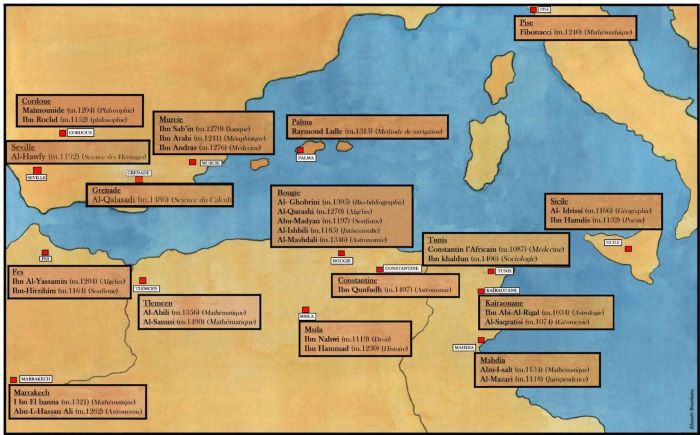

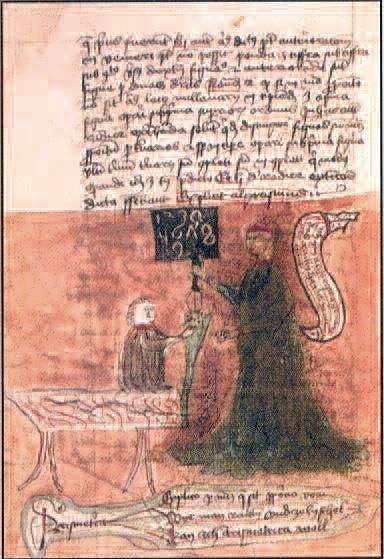

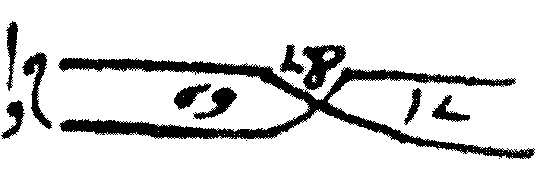

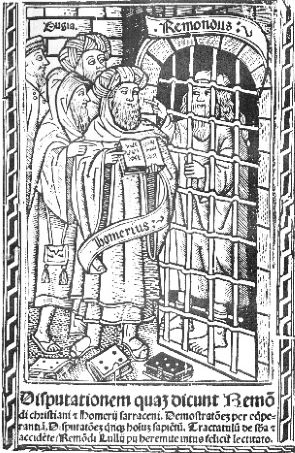

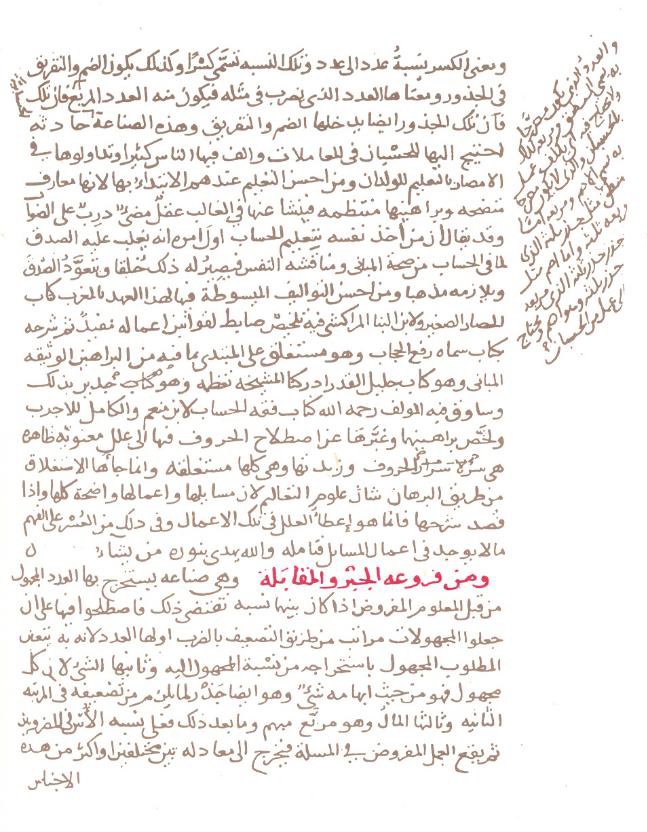

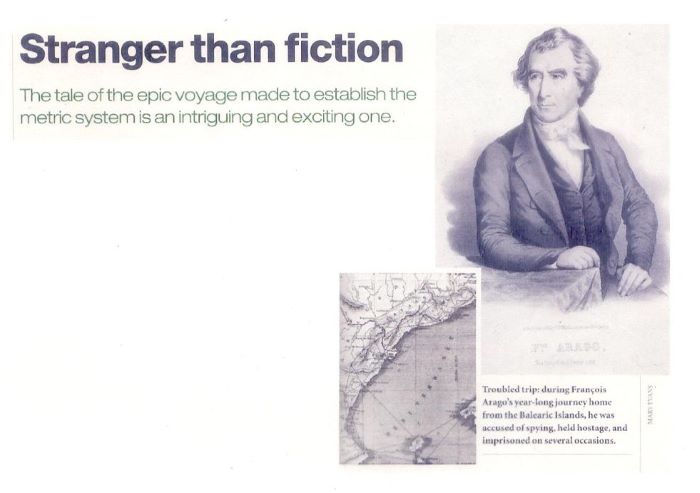

Located in the heart of the Mediterranean area, Béjaia (Bgayet in Berber, Bougie in French, Bugia in Italian, Catalan and Spanish, Buggea – Buzea in Latin), a city in Algeria which gave its name to small candles (the "bougies" ), and from which the "Arabic numerals" were popularized in Europe, had become in 1067 the new capital of the Berber Kingdom of the Hammadites. Very quickly, it will become one of the most dynamic scientific and intellectual centers in the Maghreb [1], [5]. In the middle of the 19th century, the translation (by the Baron De Slane) of the Muqqadima of the sociologist 'Ibn Khaldun (1332 – 1406) was at the origin of the first research on medieval scientific activities in the Maghreb [5]. We then discover the significant role played by this region in the production and transmission of knowledge across the Mediterranean: influence of the medicine of the Countries of Islam by Constantin l’Africain, role in the commentary of Aristode by Ibn Rochd – Averoès, dissemination of numeration, methods of calculation and commercial techniques of the Countries of Islam by the famous Italian mathematician Leonardo Fibonacci (1170 - 1240) [3], [1], use of a specific symbolism [5], influence on the logico-mathematical principles of the Catalan philosopher Raymond Lulle (1235 - 1315) [5]. On the basis of multiple cultural and scientific comments, the first part of this conference proposes to discover the medieval mathematical tradition of North Africa (computational science, algebra, geometry, astronomy, astrology, heritage sciences, commercial mathematics, music, magic squares, methods of navigation, logic, shipbuilding,…) and its environment, through the contribution of some Ulemas – Scholars of the XIth – XVth centuries (Ibn al-Banna, al-Qalasadi, Piri Reis,…). The second part will dwell on the intellectual centers, the institutions, the inter-city relations, the process of transmission,... and their relations with the Christian West. The same is true for the periods of the “dark centuries of the Maghreb” (16th – 18th centuries: al-Akhdari, Ibn Hamza, etc.) and the 19th century: knowledge available from local scholars (Lmuhub Ulahbib, al-Hafnawi, …) and activities in the Maghreb of Western mathematicians (François Arago, Eugène Dewulf, Albert Ribaucour, Auguste Bravais, André-Louis Cholesky,…) [4], [6]. Some références [1] Aïssani D.and al., Les Mathématiques à Bougie Médiévale et Fibonacci. In the book « Leonardo Fibonacci : il tempo, le opera, l’eredità scientifica », Pacini Editore (IBM Italia), Pisa, 1994, pp. 67 - 82. [2] Aïssani D., Le Mathématicien Eugène Dewulf et les Manuscrits Médiévaux du Maghreb. International Journal Historia Mathematica, N° 23, Academic Press Ed. (U.S.A.), 1996, pp. 257 – 268. [3] Aïssani D. et Valerian D., Mathématiques, Commerce et Société à Béjaïa (Bugia) au moment du séjour de Leonardo Fibonacci. International Journal “Bollettino di Storia delle Scienze Matematiche, Vol. XXIII, Fas. 2, Roma, 2003, pp. 09 – 31. [4] Verdier N., Romera-Lebret P. et Aïssani D., « Itinéraires de Savants Géomètres en Algérie au XIXe siècle, Image des Mathématiques, C.N.R.S. Ed., Paris, May 2016. [5] Aïssani D., «Les Mathématiques Maghrébines ». Revue Quaderni di Ricerca in Didattica/Mathematics, n° 2, supplemento n° 3, G.R.I.M. Ed., Palermo, 2019, pp. 19 – 35. ISSN one-line 1592 – 4424. [6] Aïssani D. et Rouxel B., Le séjour algérien du géomètre Albert Ribaucour (1886 – 1893), Revue internationale « Bulletin de la Sabix », n° 64, Ecole Polytechnique Editions, Paris, décembre 2019, pp. 109 – 126

|